When it comes to writing a good novel or story, mostly newbie writers run to the story fundamentals first. When I first started writing, I also ran to the other story elements first because I didn’t know that there is such a concept even existed as “story structure” (even plot structure or narrative story structure)

So now, you don’t have to skip these parts just because they seem hard or difficult to understand. I’m here to guide you on how to start writing your story using these unusual boring story structures. They may seem complex at first, but once you grasp them, they will solve many of your problems and save you a lot of time.

In today’s blog, we are going to study the most common and famous story structure “The Three-Act Structure.” From its concept to its idea, with simple experimental examples and a three-act structure template/diagram.

What’s the Concept of Three-Act Structure in Storytelling

The Three-Act Structure is a storytelling framework that divides a narrative into three main phases: setup, confrontation, and resolution (we going to discuss it later). It helps create a clear and engaging progression of events by introducing a protagonist, building tension through major conflicts and obstacles, and concluding with a satisfying story ending/resolution. This story structure ensures a natural flow, keeping the readers invested from beginning to end.

If you still didn’t get the concept…

3 act structure is the climax of your story, the grand finale where all the conflicts, themes, and character arcs come together in a powerful resolution. It’s the most critical part of any narrative, determining whether your story leaves an impact or falls flat. Whether you’re writing a novel, screenplay, or short story, understanding 3 act structure is worth time investment for writing an impactful story.

History of a Three-Act Structure Concept: Roots from Greece

The Three-Act story structure has its roots in Aristotelian drama, dating back to Ancient Greece. Aristotle, in his work Poetics (circa 335 BCE), described a story as having a story beginning, middle, and end (as an adept of 3 act structure) which laid the foundation for this structure.

Evolution Through History

Ancient Greek Drama (5th Century BCE)

Greek plays, particularly tragedies, followed a structure similar to the Three-Act format, consisting of:

- Prologue (Setup) – The story prologue part an introduction to the setting and story characters.

- Episodes (Confrontation) – Developed the conflict through action and dialogue.

- Exodus (Resolution) – Concluded the story with a final resolution.

Shakespearean & Classical Drama (16th–17th Century)

While Shakespearean plays followed a Five-Act Story Structure, they still contained the core three phases of setup, conflict, and resolution within the larger framework.

Modern Adaptation (19th–20th Century)

The Three-Act Structure became more formalized in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in novels, theater, and film. Playwrights like Henrik Ibsen and Anton Chekhov refined the structure, while Hollywood screenwriters (notably Syd Field in the 1970s) popularized it as a key formula for writing movies.

Today, the Three-Act Structure is a standard narrative framework used in novels, films, and screenwriting, ensuring a coherent storytelling experience.

The Three-Act Story Structure

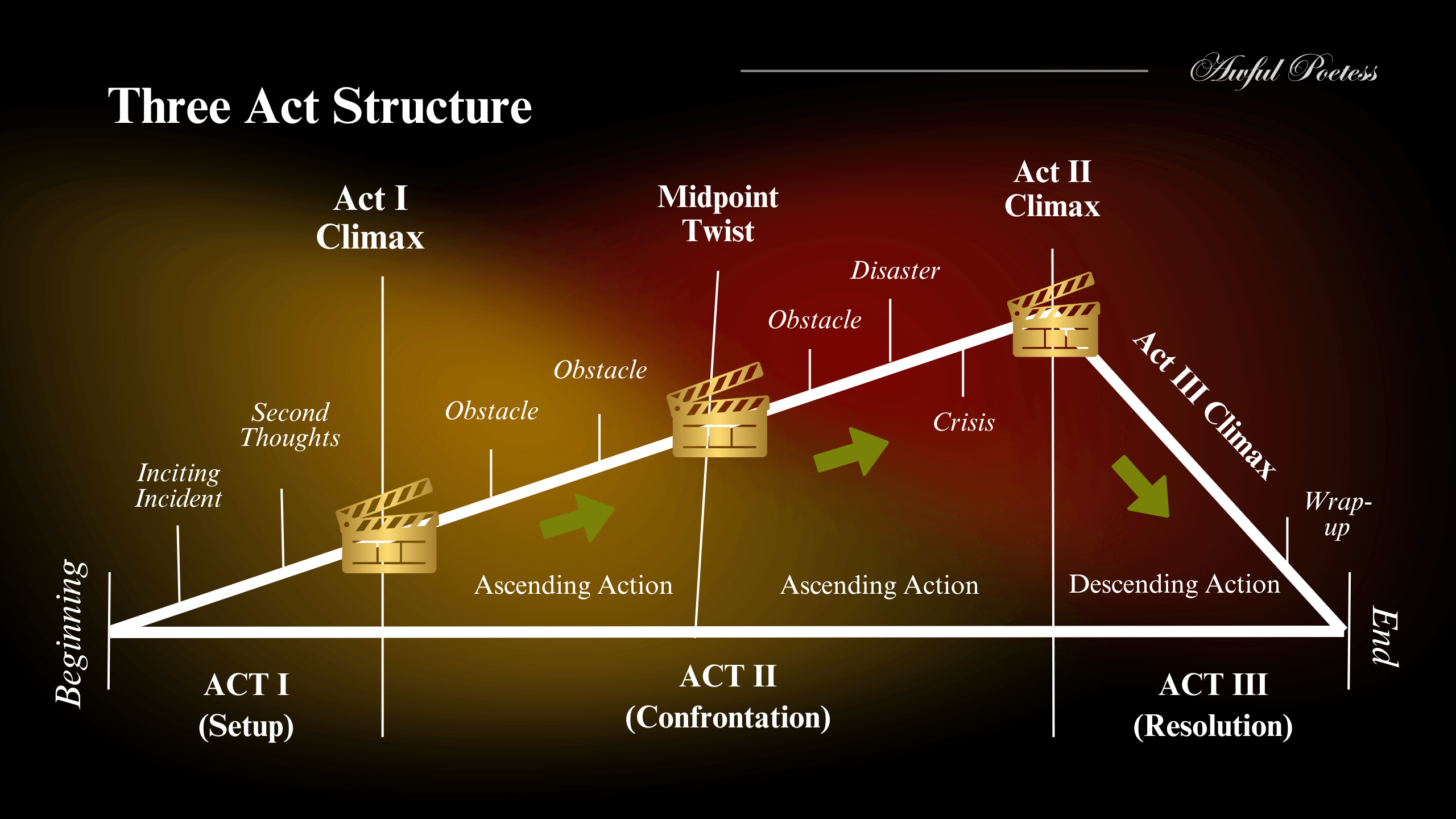

Before diving more into Act 3, let’s briefly recap the three-act structure, that created:

- Act I: The Setup – Introduces characters, setting, and the main conflict.

- Act II: The Confrontation – The protagonist faces escalating obstacles, leading to a major crisis.

- Act III: The Resolution – The climax and resolution bring the story to a close.

Key Elements of Three-Act Structure

1. The Climax: The Ultimate Showdown

The climax is the peak of dramatic tension where the protagonist faces their greatest challenge. This moment should be:

- Inevitable – Every event or scene in the story has led to this point.

- Emotional – The stakes are at their highest, ensuring a powerful payoff.

- Transformative – The protagonist undergoes a final change, proving their growth.

Example: In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the climax occurs when Harry willingly sacrifices himself, demonstrating his ultimate act of bravery before defeating Voldemort.

2. The Final Twist or Revelation

A strong three-act structure often includes a last-minute revelation or story twist that changes the protagonist’s approach. This could be:

- A hidden truth about a character.

- A shocking betrayal

- A backstory of supporting characters.

- A realisation that forces the protagonist to think differently.

Example: In Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, the famous revelation—”I am your father”—reframes Luke’s entire journey and deepens the emotional stakes.

3. The Resolution: Tying Up Loose Ends

After the climax, the resolution provides closure by:

- Showing how the protagonist has changed.

- Wrapping up story subplots and character arcs.

- Giving the readers a sense of finality, whether happy, tragic, or ambiguous (related to theme).

Example: In The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Frodo and Sam return home, but Frodo realizes he can never truly go back to his old life, reinforcing the story’s themes of sacrifice and change.

Three-Act Story Structure Example: A Quick Story Example

Here’s the quickest example of a Three-act structure method for writing a story. Let’s first draw the structure diagram in word form.

The Story Structure

ACT I – Setup (Ascending Actions)

- Beginning (The story starting)

- Inciting Incident

- Second Thought

- ACT I Climax

The ACT II – Confrontation (Ascending Actions)

- Obstacle 1

- Obstacle 2 (depends on how much you want)

- ACT II Mid-point Twist

- Obstacle 3

- Disaster

- Crisis

- ACT II Climax

ACT III – Resolution (Descending Action)

- Act III Climax

- Wrap up

- The End

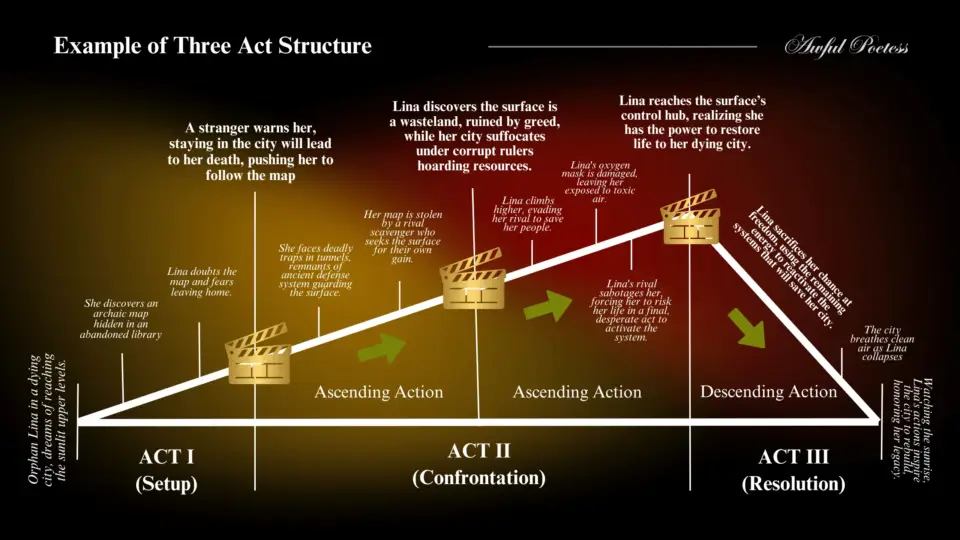

The Story Example Based on the Story Structure

ACT I – Setup Example (Ascending Actions)

- Beginning: In a dying city of shadows, an orphan little girl Lina dreams of escaping to the sunlit upper levels.

- Inciting Incident: As she grows up, she discovers an archaic map hidden in an abandoned library in her village

- Second Thought: Lina doubts that hidden map and fears leaving home because village people would find out about that map

- Act I Climax: One day she meets a strange man who warns her that staying in the city will lead to her death. He pushed her to follow the map she had found in the library.

ACT II – Confrontation Example (Ascending Actions)

- Obstacle 1: She faces deadly traps in tunnels, remnants of an ancient defence system guarding

- Obstacle 2: In her hard journey,the map is stolen by a rival scavenger who seeks the surface for their own gain.

- ACT II Mid-point Twist: Lina discovers a shocking truth about the surface is a wasteland, ruined by greed, while her city suffocates under corrupt rulers hoarding resources.

- Obstacle 3: She climbs higher on the surface to know exactly what’s going on for decades, evading her rival to save her people from more diseases.

- Disaster: Lina’s oxygen mask, which she wore as a traditional symbol believed to protect her from death, got damaged, leaving her exposed to the toxic air of her village.

- Crisis: Lina’s rival sabotages her forcing her to risk her life in a final, desperate act to activate the system.

- ACT II Climax: Lina finally reaches the surface’s control hub, realizing she has the power to restore life to her dying city.

The ACT III – Resolution Example (Descending Action)

- Act III Climax: She sacrifices her life chances, for freedom, using the remaining energy to reactivate the systems that will save her city.

- Wrap up: The dying village breathes clean air as Lina collapses

- The End: Watching the grand sunrise from the upper surface slowly removing the darkness, Lina’s actions inspire the city to rebuild, honouring her legacy.

Common Mistakes in 3 Act Structure (And How to Avoid Them)

- Rushed or Underwhelming Climax – Climax plays a major part in the three-act structure no matter if you already use mini climaxes throughout the story or if there is a mid-point climax coming in between. The main climax of a story should be a banger here. So, make sure your climax is properly built up and carries enough emotional weight. (avoid using multiple climaxes for this story structure as it does not go very well with the entire concept)

- Too Many Loose Ends – Give closure to all major character arcs and conflicts.

- Deus Ex Machina – Avoid sudden, unearned resolutions that feel forced or convenient. (surprises are good, but they should feel natural)

Final Thoughts

Act 3 is your story’s final impression, so make it count. It should deliver an emotional and thematic payoff, ensuring that the journey is worthwhile. By crafting a strong climax, a meaningful resolution, and avoiding common pitfalls, you can create a story that lingers in the minds of your audience long after they’ve turned the final page.