This blog dives into the life of Mary Shelley, the brilliant mind behind the first sci-fi gothic novel, Frankenstein. Discover the personal struggles, inspirations, and literary journey that shaped her groundbreaking work and lasting legacy.

“My dreams were all my own; I accounted for them to nobody; they were my refuge when annoyed — my dearest pleasure when free.”

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

The Godmother of Science Fiction – What’s Special about Mary Shelley?

Talking about the gothic genre or Sci-Fi literature and not discussing the legendary Mary Shelley would be an injustice to the topic. To speak of legends in literature is to speak of Mary Shelley. Her intellect pierced through the boundaries of genre, birthing worlds that redefined what fiction could be. She didn’t just write — she transcended. With a single novel, she reshaped the imagination of generations and challenged the foundations of science, ethics, and the human condition.

Mary Shelley is not just a mere name in literary history; she is its turning point. Her influence is carved into the DNA of Gothic fiction and etched into science fiction architecture. I’ve been her biggest fan since I was 13. It’s another debate about how surprised I was by her writing style, especially because my mom used to tell me that Mary Shelley used to transcribe dead people from graveyards to intensify my magical thoughts. 😒

Magic of Mary Shelley’s Writing

However, if you ask me what’s so special about Mary Shelley? I mean, there are plenty of great writers like Stephen King and William Thomas Beckford — especially in the Gothic horror genre…

But Mary? She was transformational. I found a kind of raw intellectual power in her work that doesn’t try to scare you with cheap thrills. She really unsettles you from the inside out. (Not exaggerating) but her words don’t just live on the page, they crawl under your skin and stay there. In my opinion, she didn’t write horror for the sake of ‘fear’. She wrote to explore the depth of human ambition and isolation/ She did it in a way no one had dared before.

You’ll find a warmth, a sense of closeness in Mary Shelley’s writing and that’s rare in horror. I mean, horror is horror, right? It’s supposed to scare you, not necessarily make you emotional or attached. But in Mary’s work, you do feel that connection. Or maybe it’s just me who experiences it this way, but as a reader, I think it’s incredibly important. Beyond the genre or theme, what we truly want is to connect — with the story and most of all, with the author. Her words don’t just haunt you, they hold you.

“In the middle of the night I was awakened by the cry of a child. The moment I heard it, I had a flash of intuition, which told me that this child was not my own.”

Mary Shelley — The Last Man

Birth of Mary Shelley – Daughter of the First Feminist, Pioneer of the Sci-Fi

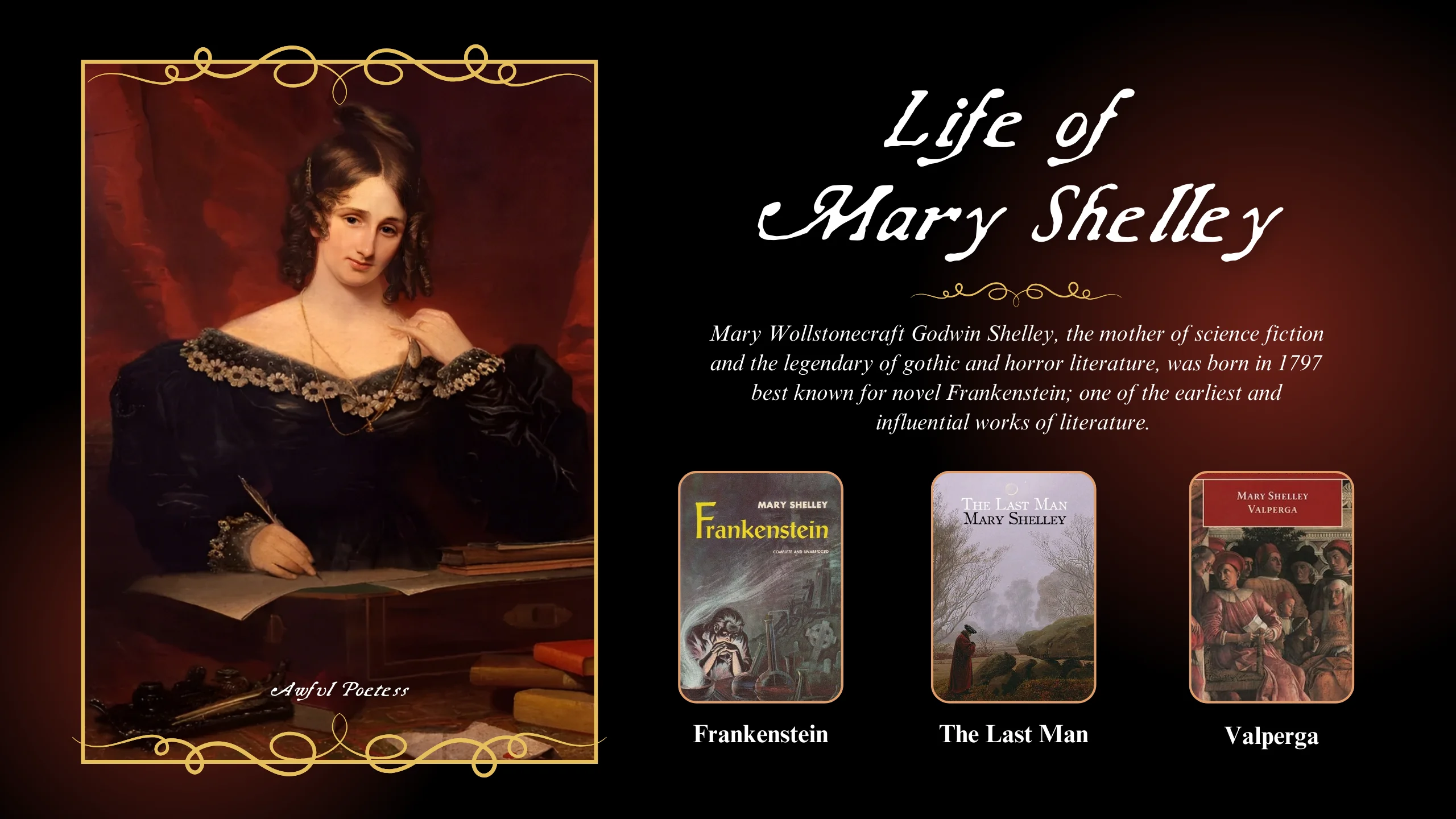

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851) is often remembered narrowly as the teenage author of the novel Frankenstein (1818), yet her contribution to literature, philosophy, and the cultural identity of Romanticism far surpasses this single act of genius. Shelley’s life, shaped by the convergence of radical enlightenment thought, Dark romantic aesthetics, and the persistent trauma of loss becomes a study of intellectual formation, gendered authorship, and political imagination.

To understand Mary Shelley is to navigate the turbulent waters of revolution, genius, death, exile, and artistic defiance.

Genesis: Born of Revolution and Radical Enlightenment (1797–1801)

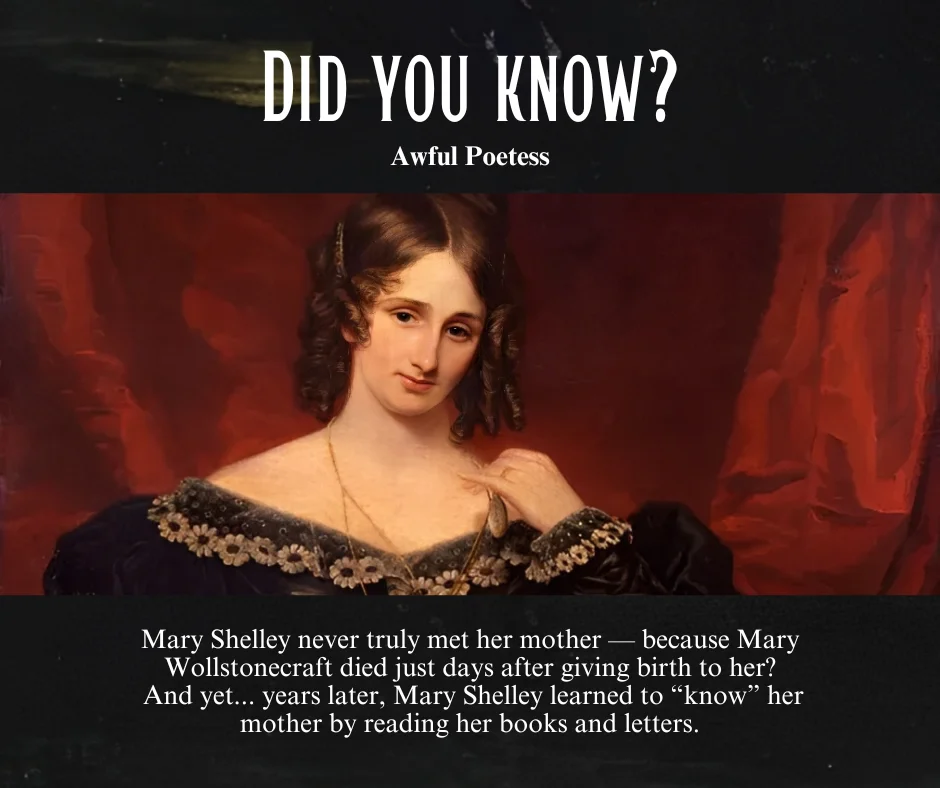

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin on August 30, 1797, in Somers Town, London. Her parentage alone would mark her as a child of radical ideas. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was the author of ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’ (1792), a foundational feminist text that championed women’s education and independence. Mary’s father, William Godwin, was also a noble philosopher and novelist best known for ‘An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice’ (1793), a major treatise on anarchist political theory.

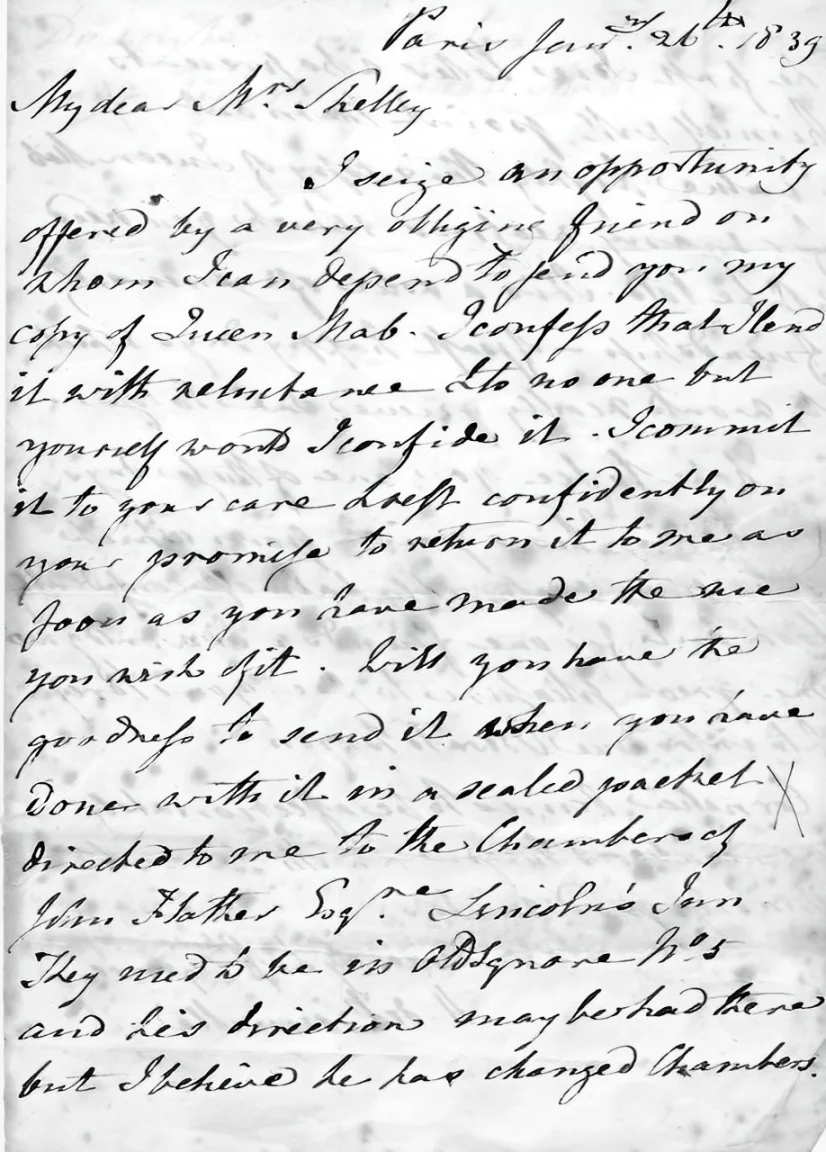

“I am very glad of my mother’s fame… It is a great consolation to me to have my mother so universally acknowledged as a woman of genius”

Mary Shelley – A Letter to Lady Byron (1819)

Tragically, Mary’s mother Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever shortly after Mary’s birth, a loss that haunted Mary throughout her life. Godwin raised Mary Shelley with an intellectual rigour rarely afforded to girls in the early 19th century. He encouraged her to engage with literature, history, and philosophy. Their household was frequented by intellectuals such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, placing Mary at the epicentre of British Romanticism from a young age.

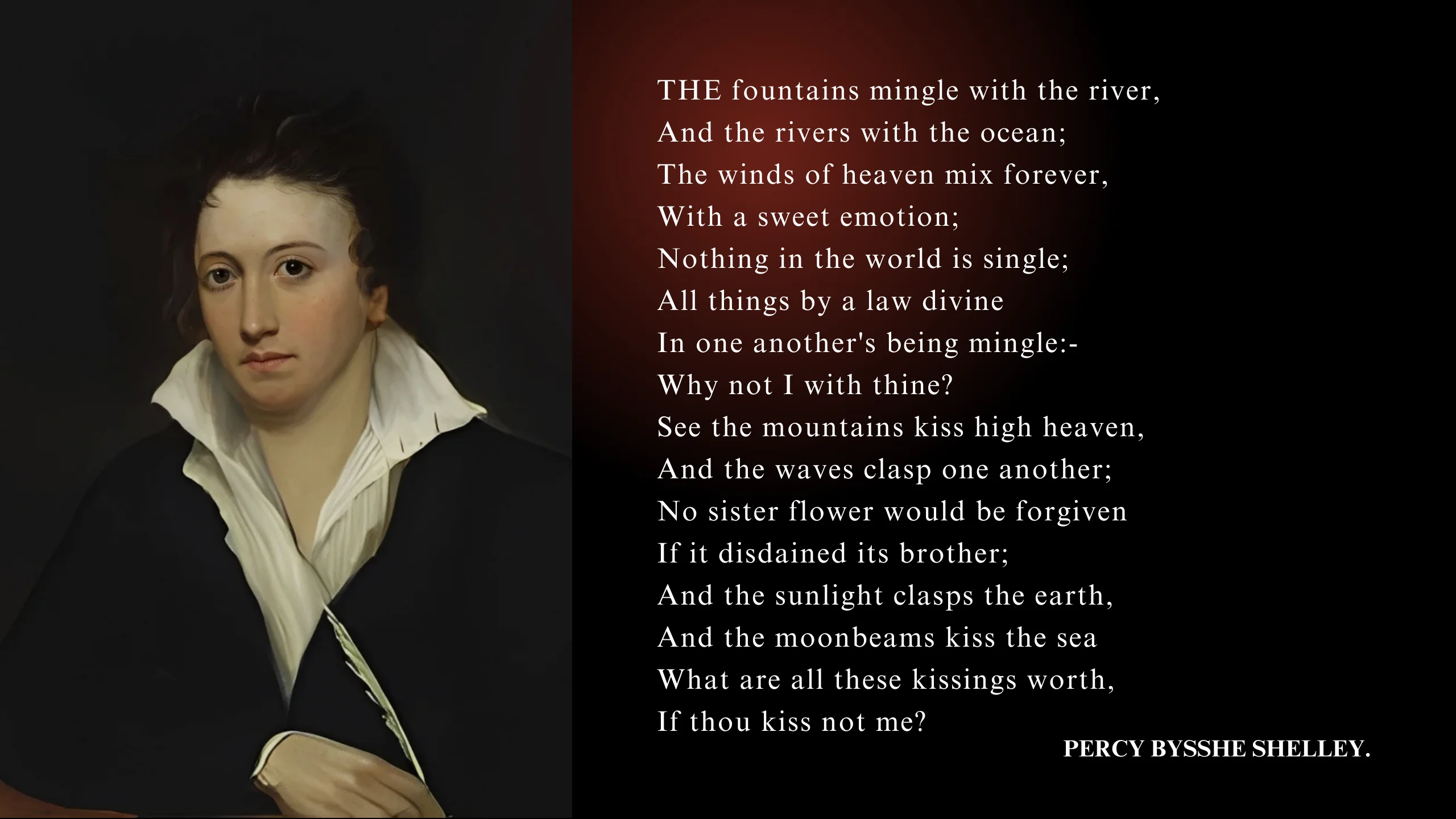

The Beginning of Mary Shelley’s Love Life with Percy Bysshe Shelley

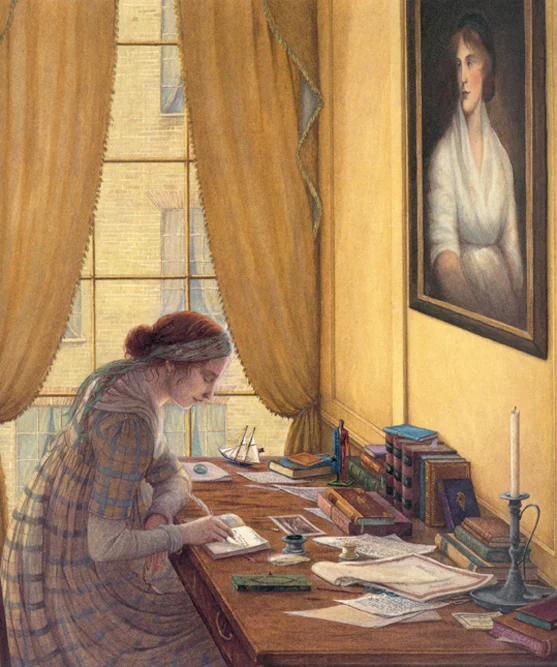

Mary’s early years were marked by emotional isolation. Her stepmother, Mary Jane Clairmont, was reportedly hostile, and Mary sought solace in books and daydreams. At age 15, she was sent to Scotland, where the natural beauty and solitude deepened her literary sensibilities.

In 1814, when Mary was just 16, she began a tumultuous relationship with the renowned English writer and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. She frequently wrote about Percy in her letters with affection and admiration, but also with a sense of vulnerability. Percy was a strong influence on Mary’s intellectual and creative development, though their relationship was marked by infidelities and personal struggles.

Percy was an atheist by belief and a political radical. He believed in nonviolent protest, free love, and the perfectibility of humanity through reason and compassion. He even had gotten kicked out of Oxford for atheism (Yes ladies and gentlemen, that was the 19th century 😌).

Marry Shelley — A Homewrecker?

Percy was already a married man with a child. But love doesn’t always wait for the right moment, Is it?

Mary and Percy’s love was anything but conventional. The fascinating thing about their love life is that it was as spooky as Mary’s life— Mary Shelley and Percy’s first meetings took place in St. Pancras Churchyard, where Mary often visited her mother’s grave for multiple reasons including writing and spending spare time.

It was among tombstones and silence where their minds connected and spirits ignited. They even spoke about philosophy, literature, and the soul. And soon, their bond blossomed into an all-consuming passion.

They ran away together in July 1814, taking Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont along for the ride. The journey across Europe was chaotic, romantic, and marked by financial hardship. Mary soon became pregnant, but the baby — a girl — died shortly after birth. This loss deeply affected her, and she later wrote in her journal:

“Dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold and that we rubbed it by the fire and it lived.”

Marry Shelley – In her Journal

Eventually, Percy’s first wife, Harriet Shelley, who had been abandoned and was pregnant with another man’s child, tragically died by suicide in 1816, drowning herself in the Serpentine River in Hyde Park. Percy, wracked with guilt but still devoted to Mary, finally married her just weeks after Harriet’s death, partially to help gain custody of his children (though he was denied custody anyway due to his radical views).

A Rumor of Percy Shelley Cheating on Mary Shelley

You know what there is even a rumour about Percy cheating on Mary even though he had a very complicated relationship with his first wife but did he actually cheat on her?

Ah, the million-dollar question. The answer? Yes — but it’s complicated.

Percy Bysshe Shelley did have emotional and possibly physical affairs while married to Mary Shelley, though the norms and ideals they both believed in blurred the traditional lines of fidelity.

Here’s the tea ☕: Percy was a vocal advocate of ‘free love’ — the idea that love shouldn’t be confined by institutions like marriage. He believed people should be free to love whomever they chose, without legal or societal restrictions.

Also, there’s long-standing speculation that Percy was emotionally (if not physically) involved with Claire, who was always around them. Letters between Percy and Claire suggest a flirtatious and intimate bond.

Even, In 1820, Percy Shelley developed a deep infatuation with a young Italian woman named Emilia Viviani. He wrote the long poem Epipsychidion in her honour, describing her as a spiritual ideal — a kind of muse. Mary was not amused. She called the poem “a beautiful rhapsody,” but she felt deeply hurt and alienated by his obsession with Emilia.

In the final years of his life, he became deeply enamoured with Jane Williams, in Italy. The partner of his friend Edward Williams. The Shelleys and the Williamses were living close to each other in San Terenzo, near Lerici. He composed a series of romantic poems dedicated to Jane, the most well-known being:

- “With a Guitar. To Jane”

- “The Serpent Is Shut Out from Paradise”

- “To Jane: The Invitation”

- “To Jane: The Recollection”

These poems clearly reveal emotional intensity and admiration — Shelley refers to Jane.

And like that, there are many stories of Percy cheating on his wife Mary Shelley.

So, did he cheat?

By modern standards? Yes. Emotionally for sure, physically probably.

By his own philosophical beliefs? He wouldn’t call it ‘cheating’, he believed love was bigger than rules and parameters.

And Mary?

She loved him fiercely and faithfully. Despite the betrayals, heartbreak, and grief, she stood by his side in life and death. She edited his work, raised his son, and kept his memory alive. But in her journals and letters, you can see the ache. She may have accepted free love intellectually, but she longed for exclusive devotion — something Percy couldn’t fully offer.

The Famous Story of Percy Shelley’s Unburned Heart

In 1822, at just 29, Percy Shelley drowned while sailing off the coast of Italy. A storm overtook his boat, Don Juan, and his body washed ashore ten days later. When he was cremated on the beach, legend says his heart would not burn. A friend reportedly pulled it from the fire and gave it to Mary, who kept it wrapped in a copy of Adonais, the elegy Percy had written for Keats. At just 24, Mary was a widow with a surviving son, Percy Florence. She kept his scorched heart in her desk drawer for the rest of her life. They only found his heart after she died.

Mary lived on, refusing to remarry. She devoted herself to preserving Percy’s legacy, editing and publishing his works, and raising their only surviving child. Her own writings continued, though none reached the fame of Frankenstein. Yet in grief and solitude, she remained his — always.

The Backstory of Frankenstein Or Modern Prometheus (1816–1818)

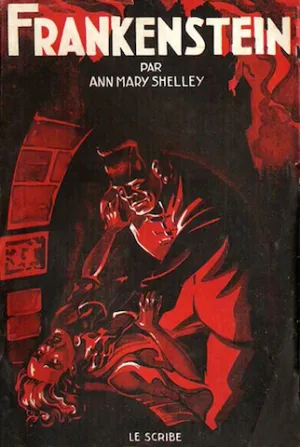

In the fateful summer of 1816, Mary, Percy, Claire, Lord Byron, and John Polidori gathered at Villa Diodati near Lake Geneva. Byron proposed a ghost story contest. Out of that challenge, Mary conceived Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus (She was only 18 years old at that time).

The legendary novel was published anonymously in 1818, with a preface by Percy Shelley, leading many to assume he was the original author of ‘Frankenstein’. However, Mary’s philosophical voice is unmistakable. Frankenstein is not merely a Gothic horror story! It is a meditation on the Enlightenment’s promises and dangers, on the ethics of scientific creation, and on the agony of alienation. In the Creature’s eloquence and despair, Shelley indicts the cold rationalism of her age, presenting a new kind of myth that bridges the classical and the modern.

After Frankenstein, she remained intellectually productive and wrote many other novels too such as Valperga (1823), The Last Man (1826), and Lodore (1835), and penned numerous biographical and travel writings.

Later Years: Reputation, Reclamation, and Resistance (1823–1851)

Returning to England in 1823, Mary lived a financially strained life. She focused on her son’s education, continued writing, and quietly navigated the patriarchal constraints of the literary establishment. Notably, she declined romantic advances from prominent men like Prosper Mérimée and Washington Irving, perhaps finding freedom in solitude.

She remained politically aware but tempered her radical expressions. We find her late fiction more focused on domestic and moral themes. But beneath them, her critique of patriarchy and power remained sharp.

In 1831, she revised Frankenstein for a new edition and softened some of its more radical elements. Nonetheless, it was clear that the novel had grown in mythic stature.

Death of Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley died of a brain tumour on February 1, 1851, at age 53, surrounded by her son and daughter-in-law. She was buried at St. Peter’s Church in Bournemouth, along with the remains of Percy’s heart—said to have been saved from his funeral pyre.

Mary Shelley’s Legacy and Intellectual Resonance

Mary Shelley’s life intersects with the grand intellectual debates of her age: the promises and perils of science, the limits of Romantic individualism, the moral imagination of literature, and the place of women in public thought.

Her vision in Frankenstein anticipated modern anxieties around artificial intelligence (AI), bioethics, and the “hubris of creation.” Moreover, as literary scholar Anne K. Mellor has argued, Shelley “created the genre of science fiction,” not through machines, but through ideas.

Yet it is perhaps her philosophical subtlety, her resilience, and her lifelong commitment to writing as a mode of thinking that cements her place in the pantheon—not just as a writer of horror, but as a philosopher of modernity.

Conclusion: The Woman Behind the Myth

Mary Shelley was more than the author of Frankenstein. She was a thinker forged in revolution and grief, a mother shaped by loss, and a writer who, through subtle subversion, planted ideas that would take root in feminist, posthumanist, and political thought centuries later.

Her life was a novel in itself—crafted not merely in pages, but in ideas, tragedy, love, and rebellion.

Selected Sources & Further Reading

- Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. Routledge, 1989.

- Spark, Muriel. Mary Shelley: A Biography. Phoenix, 1987.

- Poovey, Mary. “My Hideous Progeny: The Lady and the Monster.” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 2 (1991).

- Sunstein, Emily W. Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

- Clemit, Pamela (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818 & 1831 editions).

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future. Faber & Faber, 2002.

- Blumberg, Jane. Mary Shelley’s Early Novels: ‘This Mortal Immortality’. Macmillan, 1993.

Some Quick FAQs About Mary Shelley’s Life

Mary Shelley is most famous for writing the novel “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus,” first published in 1818. It is considered one of the earliest examples of a science fiction novel.

At 24, Mary Shelley faced a major tragedy—the death of her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, who drowned in a storm while sailing in Italy in 1822. His death deeply affected her.

Mary Shelley typically published under her real name, Mary Shelley, especially after she gained recognition. However, when Frankenstein was first published in 1818, it was anonymously released.

Mary Shelley died of a brain tumour in 1851, at the age of 53. In the final years of her life, she suffered from chronic illness, including frequent headaches and paralysis in parts of her body, which were later attributed to the tumour.

Mary Shelley did not receive a formal education in a traditional school setting. Instead, she was educated at home by her father, William Godwin, who was a prominent writer and philosopher.

Mary Shelley’s most well-known portrait was painted by Richard Rothwell in 1840. It’s a posthumous-style oil portrait that presents her in a thoughtful and dignified pose.