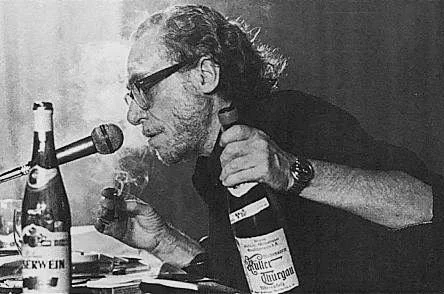

Are you a fan of Franz Kafka or Charles Bukowski? Well, if you are, here is the blog on the similarities between Kafka and Bukowski to know more about their life and work. A resemblance like a father and a son!

If anyone ever asked me about two literary geeks who feel vaguely similar but are actually galaxies apart, I’d say: Franz Kafka and Charles Bukowski.

And yes, it’s true! Even though Bukowski had nothing in common with anybody, it’s hard to even imagine a connection between him and Kafka in any meaningful way.

Yet somehow, my overthinking brain pulled a classic stunt and whispered:

“What if they were father and son?”

I know. Ridiculous. One is like water; slow, suffocating, existential. The other? Pure fire; loud, drunk, and always five seconds away from starting a ring fight. 🥊

But still, here I am, connecting dots that don’t exist. (Forgive me, guys! I’m just a jobless person with enough free time to write blogs about topics that absolutely nobody asked for : )

But anyway, let’s rewind for a second:

Why did I even think of this twisted literary family tree in the first place?

And more importantly:

What can we learn from this chaotic, steamy collision of Franz Kafka and Charles Bukowski (as a metaphor for life itself)?

Let’s dig in, shall we?

Bukowski, The Son Of Kafka – A Thought

We all know that Charles Bukowski’s life ran entirely opposite to that of Kafka and the Kafkaesque. Kafka was all anxious, bullied kid in school, a suffocating and silent bureaucracy hater. Bukowski? He was pouring beer on that very paperwork, flipping off authority with a cigarette hanging from his mouth. So why on earth do I keep thinking of them as father and son?

Maybe it’s not about lifestyle, but something deeper? Like a hidden emotional DNA.

I mean, let’s be honest, if we’re picking a “literary dad” for our chad Bukowski, Henry Miller fits the bill better. Bukowski practically worshipped the man. He even called him his “God,” praised his freedom, his rawness, his guts to write about sex, dirt, chaos, and joy with zero apologies. That influence is undeniable.

Bukowski Never Wanted To Be Franz Kafka

Charles Bukowski did read Franz Kafka and had a nuanced, somewhat ambivalent view of his work. While Bukowski also acknowledged Kafka’s literary significance, he often expressed reservations about Kafka’s style and thematic focus.

In a letter from late November 1962, Bukowski recommended Franz Kafka over Henry James, which indicated a preference for Kafka’s work in certain contexts. This suggests that, despite his critiques, Bukowski found value in Kafka’s writing.

However, Bukowski did criticise Kafka’s writing hard for being overly cerebral and detached from the visceral realities that Bukowski himself preferred to explore (of course, he had to have these excepted views about him; they were many lifetimes apart from each other). Charles always favoured raw, unfiltered expressions of life’s hardships, often grounded in the experiences of everyday people. This preference is evident in his own writing style, which contrasts with Kafka’s more abstract and existential themes.

On the other hand, Franz Kafka, fortunately or unfortunately, never got the chance to read Bukowski’s work. So, we’re left in the dark about what he would’ve thought. Would he have been horrified by Bukowski’s raw, unfiltered grit? Or secretly admired the brutal honesty behind the chaos? We’ll never know.

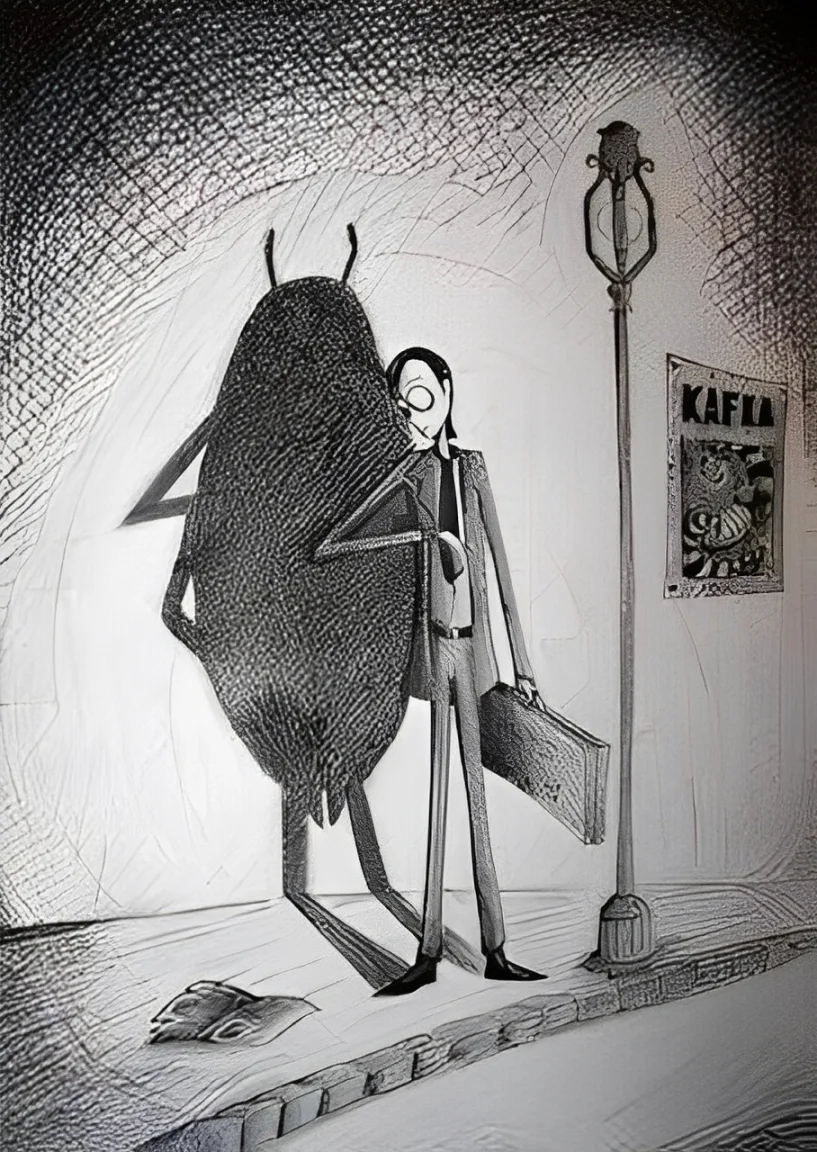

When the Absurd Births the Profane: Why Bukowski Could Be Kafka’s Literary Son

We grow up thinking we’ll become copies of our fathers (or we fight like hell not to). Either way, their blood is in our ink. Bukowski didn’t write like Kafka, but he felt like him, deep in the gut where art either festers or explodes. He never wanted to be him, but somehow ended up being him, with the opposite writing style and sense of humour.

And isn’t that what sons do? They take the quiet pain of their fathers and scream it out loud. Kafka wrote as if life were a courtroom and he was always on trial. Bukowski wrote like life was a fight, and he kept getting up. Both were losing. Both kept writing!

We inherit more than we admit. Not the style. Not the form. But the ache. The disillusionment. The need to find some kind of truth in the rubble. Kafka questioned meaning; Bukowski pissed on it. And in that act, he became a kind of bastard son—unwanted, maybe, but born out of the same existential bed.

How Charles Bukowski’s Life Mirrors Franz Kafka’s?

The Tale of Alienation and Isolation in Franz Kafka and Charles Bukowski’s Lives

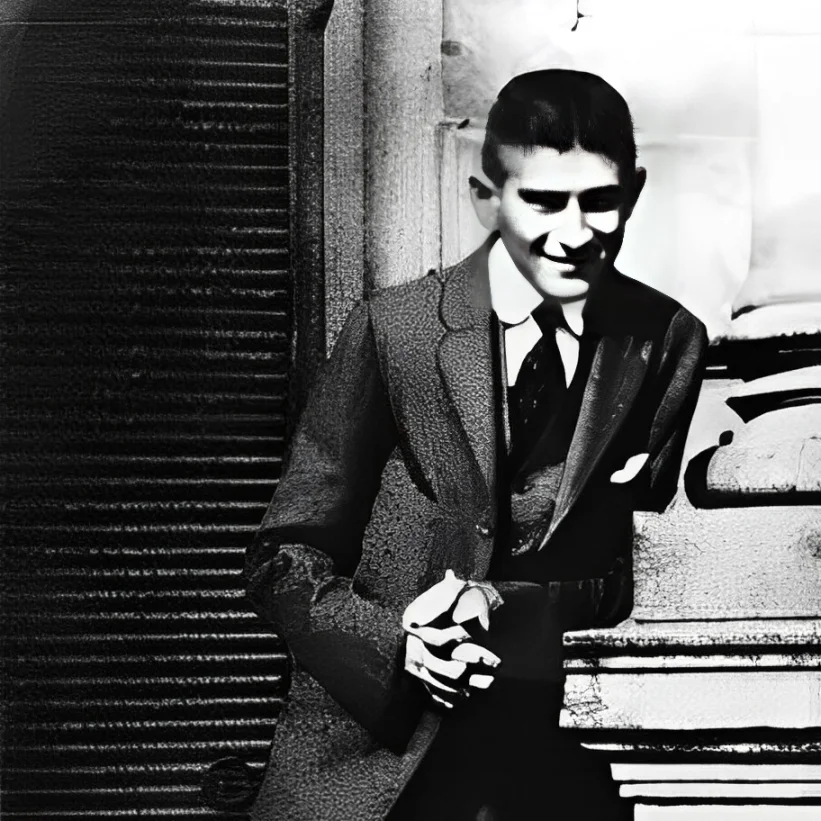

- Kafka: Felt estranged from his family, Jewish identity, and the bureaucracy he worked. Franz suffered more internally in his early life.

- Bukowski: On the other hand, Charles Bukowski’s life was much terrible because of the physical abuse. Grew up in an abusive household, felt like an outcast due to his severe acne, poverty, and later, his disdain for 9–5 jobs.

Both men lived like outsiders trapped inside systems they despised.

Difficult Father Relationships and Childhood

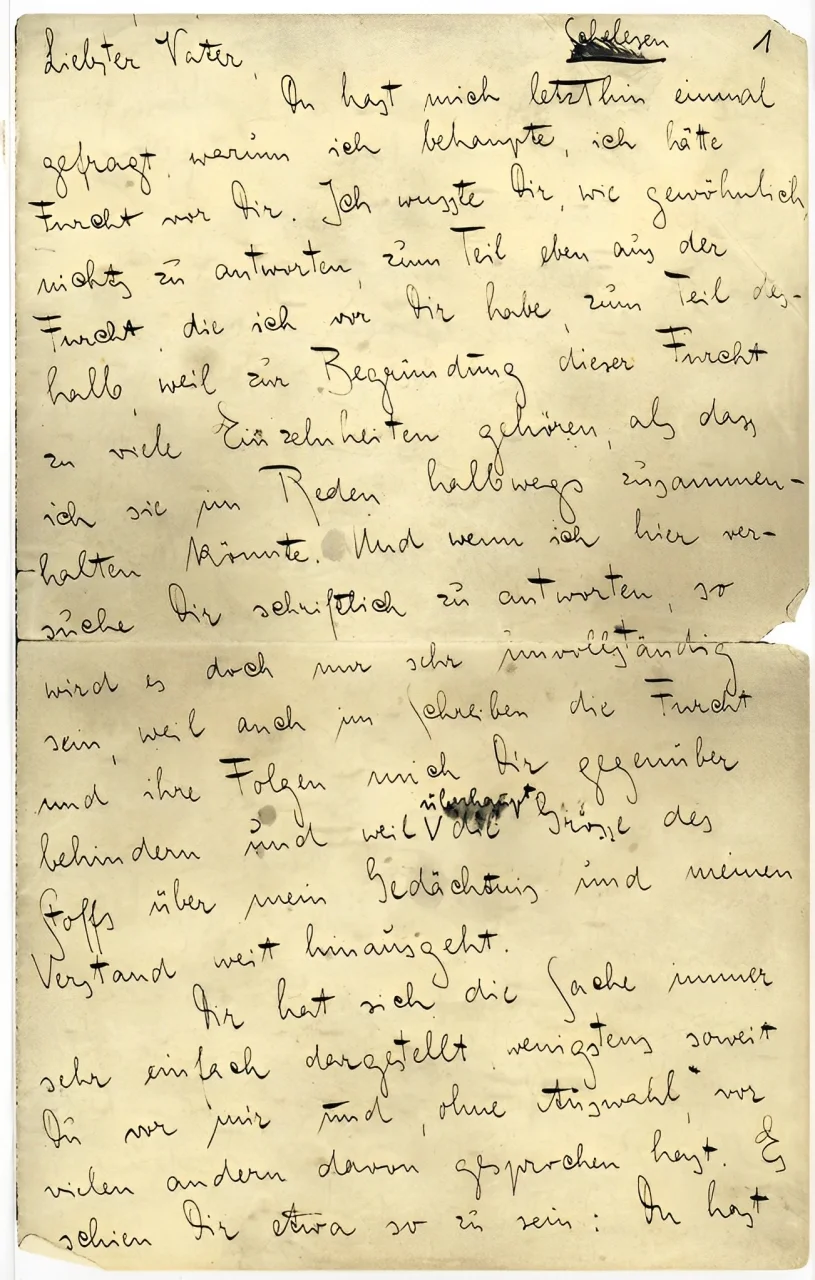

- Kafka: His relationship with his father was famously toxic; it shaped his neuroses and sense of inadequacy.

- Bukowski: Physically and emotionally abused by his father, he never forgave him, and this rage seeps into all his early work.

Both had wounded inner children who never got closure. And it is widely seen in their works.

Dead-end, Depressing Jobs

- Kafka: Insurance clerk, spent 14 years at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, known for his precision and dedication. Then went home to write dark, surreal stories about powerlessness and fear.

- Bukowski: Postal worker. Loud desperation, worked at the U.S. Post Office nearly 12 years, quit at 49 after getting a publishing deal, then wrote Post Office in 3 weeks based on that job.

Same soul-killing routine. Kafka internalised the absurdity; Bukowski howled at it.

Chronic Illness & Mental Anguish

- Kafka: Diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1917, he struggled with anxiety and depression throughout his life, which worsened until he died in 1924.

- Bukowski: Battled lifelong depression and severe alcoholism, which affected his relationships and work; struggled with social anxiety but often hid it behind a tough, rebellious persona.

Lack of Fame in Youth – The Biggest Misery

Neither man was fully recognised while young. Kafka died unpublished by choice. Bukowski barely scraped by till his 50s. Franz published only a few short stories during his lifetime, never completing a novel for publication. He instructed his close friend Max Brod to destroy all his unpublished manuscripts after his death, a wish Brod famously ignored.

Whereas Bukowski struggled for decades, publishing mostly in small literary magazines and underground presses. He worked low-paying jobs, barely able to support himself as a writer. His first major book, Post Office, was published when he was 49, after years of rejection. After that breakthrough, his cult following grew steadily, but mainstream literary fame came late, mostly in his 50s and 60s.

The Major, Significant and Loud Difference Between Both Writers

I’ve already given you some hints about how their writing styles were very different from each other, but to capture the contrast even more clearly, here are some key parameters to notice in the works of these two literary gods, Franz Kafka and Charles Bukowski:

Language: Abstract vs. Brutal

- Franz Kafka: Precise yet frightened, abstract and famously metaphorical. His prose builds slow, creeping dread. Everything is uncertain and unconscious. You don’t know what’s real or symbolic. “A man is transformed into a giant insect…” but why? It’s a symbol, a riddle, a nightmare.

- Bukowski: Raw, blunt, literal. There are no metaphors to decode. It’s all on the surface — dirty, vulgar, real. “I was a bum. I drank. I fucked. I worked a shitty job. Then I went home and drank more.”

Kafka: art as parable.

Bukowski: art as the punch in the gut.

Tone: Fear vs. Defiance

- Franz writes like a man terrified of the system, a mouse in a bureaucratic maze.

Kafka: “What if I don’t belong here?”

- Charles writes like a man who hates the system and tells it to go fuck itself.

Bukowski: “Of course I don’t belong here — FU*K OFF!”

Setting: Surrealism vs. Gutter Realism

- Kafka’s worlds are surreal, dreamlike, and foggy. You’re never quite sure where you are: an endless hallway, a nonsensical trial. Honestly, his stories never needed detailed settings; in fact, if Kafka had focused too much on realistic settings, he might have lost the intense focus on the themes that really matter in his work. The vagueness strengthens his exploration of alienation and absurdity.

- Bukowski’s world is concrete: dive bars, strip clubs, shitty apartments, post offices. There’s nothing imaginary, just grit and whiskey, yet real af.

Purpose in Stories: Philosophical Horror vs. Personal Survival

- Kafka’s writing explores existential anxiety — what it means to be powerless, small, crushed by unseen forces. He spent time understanding himself, yet never understood still managed to give us a lesson of “finding purpose, a solid rock purpose in life” to not get fucked up by anyone as he got!

- Bukowski’s writing is about surviving one more day without losing your mind. His work presents the nihilistic side of philosophy, where nothing truly matters, yet everything still counts! Bukowski never tried to teach explicit philosophical lessons to us; instead, he shared his only true belief, his “philosophy of trying,” the raw, stubborn act of pushing through life’s pain and chaos without any grand meaning but by being LEGIT.

So, in short:

Kafka asked: “What is the meaning of this suffering?”

Bukowski said: “There is none. You just drink, write, and suffer through it.”

Narrator Style: Nervous vs. Numb

- Kafka’s narrators are always deeply introspective, neurotic, confused, and questioning everything.

- Bukowski’s narrators (like Chinaski) are detached, cynical, and mostly just trying not to care too much.

The Lesson and Purpose of This Literary Observation

I confessed that at the end of the blog, we would know the answers to these two questions:

- Why did I even think of this twisted literary family tree in the first place?

- What can we learn from this chaotic collision of Kafka and Bukowski?

So the first answer is: if you’re a fan of Kafka (which, let’s be honest, you probably are!) Charles Bukowski could be the best example for you as a kind of spiritual opposite. Where Kafka internalised the absurdity of the world, Bukowski externalised it. Kafka feared the system; Bukowski laughed in its face. Both men wrote from the same dark place, but they dealt with it in radically different ways.

So, there’s no single way to deal with pain, powerlessness, or meaninglessness. One man turned it into quiet nightmares, the other into loud confessions. Whether you whisper your truth or scream it, what matters is that you tell it!

In my opinion, this unlikely pairing sticks in my mind because it shows how two writers, with entirely different personas, styles, thoughts, and even eras, can offer a 90-degree angle on reality. They prove there’s no single path to deal with the same human condition.

You could be like Kafka today: afraid to show your insane talent to the world, stuck in the loop of thinking you’re not enough, that maybe this quiet suffering is just your fate.

But there’s also Charles mode; the switch you can flip. The one where you stop caring about public opinion and just do your shit the way you want. Loud. Unfiltered. Unapologetic.